The first known case of humans going to court over investment losses triggered by autonomous machines will test the limits of liability.

Robots are getting more humanoid every day, but they still can’t be sued.

So a Hong Kong tycoon is doing the next best thing. He’s going after the salesman who persuaded him to entrust a chunk of his fortune to the supercomputer whose trades cost him more than $20 million.

The case pits Samathur Li Kin-kan, whose father is a major investor in Shaftesbury Plc, which owns much of London’s Chinatown, Covent Garden and Carnaby Street, against Raffaele Costa, who has spent much of his career selling investment funds for the likes of Man Group Plc and GLG Partners Inc. It’s the first-known instance of humans going to court over investment losses triggered by autonomous machines and throws the spotlight on the “black box” problem: If people don’t know how the computer is making decisions, who’s responsible when things go wrong?

“People tend to assume that algorithms are faster and better decision-makers than human traders,” said Mark Lemley, a law professor at Stanford University who directs the university’s Law, Science and Technology program. “That may often be true, but when it’s not, or when they quickly go astray, investors want someone to blame.”

The timeline leading up to the legal battle was drawn from filings to the commercial court in London where the trial is scheduled to begin next April. It all started over lunch at a Dubai restaurant on March 19, 2017. It was the first time 45-year-old Li, met Costa, the 49-year-old Italian who’s often known by peers in the industry as “Captain Magic.” During their meal, Costa described a robot hedge fund his company London-based Tyndaris Investments would soon offer to manage money entirely using AI, or artificial intelligence.

Developed by Austria-based AI company 42.cx, the supercomputer named K1 would comb through online sources like real-time news and social media to gauge investor sentiment and make predictions on U.S. stock futures. It would then send instructions to a broker to execute trades, adjusting its strategy over time based on what it had learned.

The idea of a fully automated money manager inspired Li instantly. He met Costa for dinner three days later, saying in an e-mail beforehand that the AI fund “is exactly my kind of thing.”

Over the following months, Costa shared simulations with Li showing K1 making double-digit returns, although the two now dispute the thoroughness of the back-testing. Li eventually let K1 manage $2.5 billion—$250 million of his own cash and the rest leverage from Citigroup Inc. The plan was to double that over time.

But Li’s affection for K1 waned almost as soon as the computer started trading in late 2017. By February 2018, it was regularly losing money, including over $20 million in a single day—Feb. 14—due to a stop-loss order Li’s lawyers argue wouldn’t have been triggered if K1 was as sophisticated as Costa led him to believe.

Li is now suing Tyndaris for about $23 million for allegedly exaggerating what the supercomputer could do. Lawyers for Tyndaris, which is suing Li for $3 million in unpaid fees, deny that Costa overplayed K1’s capabilities. They say he was never guaranteed the AI strategy would make money.

Sarah McAtominey, a lawyer representing Li’s investment company that is suing Tyndaris, declined to comment on his behalf. Rob White, a spokesman for Tyndaris, declined to make Costa available for interview.

The legal battle is a sign of what’s in store as AI is incorporated into all facets of life, from self-driving cars to virtual assistants. When the technology misfires, where the blame lies is open to interpretation. In March, U.S. criminal prosecutors let Uber Technologies Inc. off the hook for the death of a 49-year-old pedestrian killed by one of its autonomous cars.

Robot Investors

AI hedge fund managers are beating human peers, but not stock benchmarks

Source: Eurekahedge, Hedge Fund Research, Inc., Bloomberg

2019 gains through March for every $100 invested in 2014; S&P 500 returns are with dividends reinvested; *HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index

In the hedge fund world, pursuing AI has become a matter of necessity after years of underperformance by human managers. Quantitative investors—computers designed to identify and execute trades—are already popular. More rare are pure AI funds that automatically learn and improve from experience rather than being explicitly programmed. Once an AI develops a mind of its own, even its creators won’t understand why it makes the decisions it makes.

“You might be in a position where you just can’t explain why you are holding a position,” said Anthony Todd, the co-founder of London-based Aspect Capital, which is experimenting with AI strategies before letting them invest clients’ cash. “One of our concerns about the application of machine-learning-type techniques is that you are losing any explicit hypothesis about market behavior.”

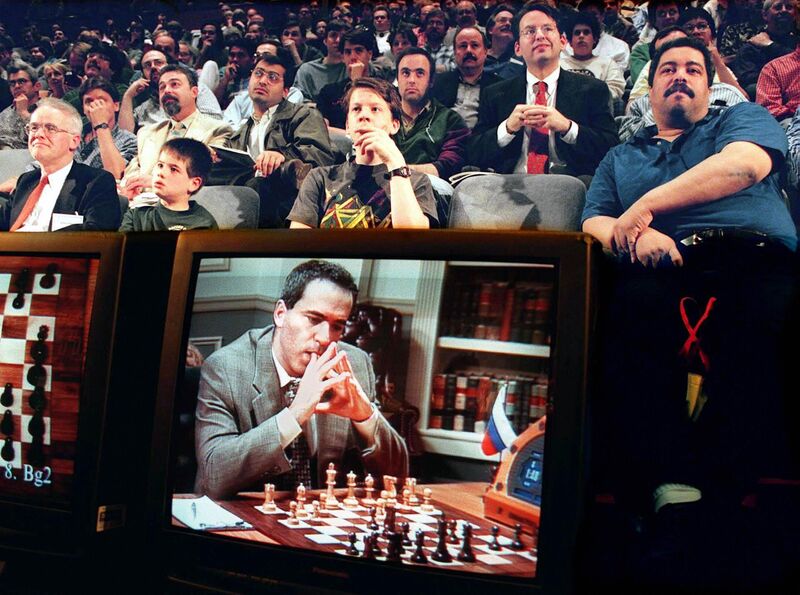

Li’s lawyers argue Costa won his trust by hyping up the qualifications of the technicians building K1’s algorithm, saying, for instance, they were involved in Deep Blue, the chess-playing computer designed by IBM Corp. that signaled the dawn of the AI era when it beat the world champion in 1997. Tyndaris declined to answer Bloomberg questions on this claim, which was made in one of Li’s more-recent filings.

Speaking to Bloomberg, 42.cx founder Daniel Mattes said none of the computer scientists advising him were involved with Deep Blue, but one, Vladimir Arlazarov, developed a 1960s chess program in the Soviet Union known as Kaissa. He acknowledged that experience may not be entirely relevant to investing. Algorithms have gotten really good at beating humans in games because there are clear rules that can be simulated, something stock markets decidedly lack. Arlazarov told Bloomberg that he did give Mattes general advice but didn’t work on K1 specifically.

Inspired by a 2015 European Central Bank study measuring investor sentiment on Twitter, 42.cx created software that could generate sentiment signals, said Mattes, who recently agreed to pay $17 million to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to settle charges of defrauding investors at his mobile-payments company, Jumio Inc., earlier this decade. Whether and how to act on those signals was up to Tyndaris, he said.

“It’s a beautiful piece of software that was written,” Mattes said by phone. “The signals we have been provided have a strong scientific foundation. I think we did a pretty decent job. I know I can detect sentiment. I’m not a trader.”

There’s a lot of back and forth in court papers over whether Li was misled about K1’s capacities. For instance, the machine generated a single trade in the morning if it deciphered a clear sentiment signal, whereas Li claims he was under the impression it would make trades at optimal times during the day. In rebuttal, Costa’s lawyers say he told Li that buying or selling futures based on multiple trading signals was an eventual ambition, but wouldn’t happen right away.

For days, K1 made no trades at all because it didn’t identify a strong enough trend. In one message to Costa, Li complained that K1 sat back while taking adverse movements “on the chin, hoping that it won’t strike stop loss.” A stop loss is a pre-set level at which a broker will sell to limit the damage when prices suddenly fall.

That’s what happened on Valentine’s Day 2018. In the morning, K1 placed an order with its broker, Goldman Sachs Group Inc., for $1.5 billion of S&P 500 futures, predicting the index would gain. It went in the opposite direction when data showed U.S. inflation had risen more quickly than expected, triggering K1’s 1.4 percent stop-loss and leaving the fund $20.5 million poorer. But the S&P rebounded within hours, something Li’s lawyers argue shows K1’s stop-loss threshold for the day was “crude and inappropriate.”

Li claims he was told K1 would use its own “deep-learning capability” daily to determine an appropriate stop loss based on market factors like volatility. Costa denies saying this and claims he told Li the level would be set by humans.

In his interview, Mattes said K1 wasn’t designed to decide on stop losses at all—only to generate two types of sentiment signals: a general one that Tyndaris could have used to enter a position and a dynamic one that it could have used to exit or change a position. While Tyndaris also marketed a K1-driven fund to other investors, a spokesman declined to comment on whether the fund had ever managed money. Any reference to the supercomputer was removed from its website last month.

Investors like Marcus Storr say they’re wary when AI fund marketers come knocking, especially considering funds incorporating AI into their core strategy made less than half the returns of the S&P 500 in the three years to 2018, according to Eurekahedge AI Hedge Fund Index data.

“We can’t judge the codes,” said Storr, who decides on hedge fund investments for Bad Homburg, Germany-based Feri Trust GmbH. “For us it then comes down to judging the setups and research capacity.”

But what happens when autonomous chatbots are used by companies to sell products to customers? Even suing the salesperson may not be possible, added Karishma Paroha, a London-based lawyer at Kennedys who specializes in product liability.

“Misrepresentation is about what a person said to you,” she said. “What happens when we’re not being sold to by a human?”