OCTOBER 27, 1988

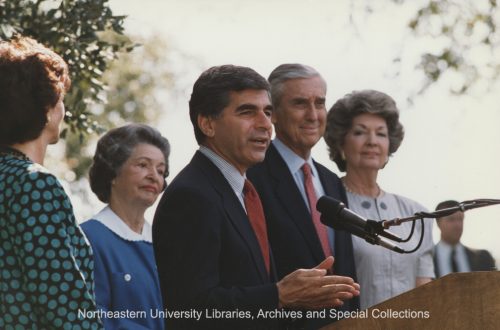

WASHINGTON — EARLY in February 1987, Jerome Grossman, a prominent Boston Democrat, got a phone call from the governor. Michael Dukakis was thinking about running for president. Invited to Mr. Dukakis’s home, Mr. Grossman prepared a memo outlining eight possible paths to the Democratic nomination, based on his experience in several presidential campaigns.

“Are you trying to tell me something?” Dukakis asked, reading the memo. “You’re trying to tell me that I don’t fit any of the eight paths?”

“That determination is up to you to make,” his guest replied.

“Jerry, this is Mike Dukakis,” the caller said. “I know I don’t fit any of your eight paths, but I’m going to create a ninth one.”

And so Michael Dukakis, a third-term governor of the commonwealth of Massachusetts, began his spectacular rise to become the Democratic Party’s nominee for the presidency of the United States. His bid for the White House says a lot about Dukakis.

He has a reputation for being an efficient administrator, with a fine eye for detail and emerging skills as a compromiser. A very private man, Dukakis campaigns long and hard. He is by most accounts deeply committed to the concerns of average Americans, and is convinced that government can and should lend a helping hand.

“What we’ve learned about him from the campaign is what many folks knew before the campaign,” says Ira Jackson, Dukakis’s former tax chief, who has known the governor 25 years. Mr. Jackson uses words like steady, unflappable, and indefatigable to describe Dukakis.

“He has held down the governorship of a major industrial state … run for president, maintained his sanity and good humor, kept his family together, and raised and spent $150 million,” Jackson says. “If you get a distance from it, it is a pretty awesome set of challenges.”

True, others say, but the point is not to survive. It’s to win.

A Boston insider laments: “On being competent, he deserves a lot of credit – but that won’t get you elected president.”

Sources close to the governor say there were a number of factors that led Dukakis to run for the nomination.

The “Massachusetts miracle” – at that time the state’s economic performance was a shining star – burnished his record as a skillful and innovative chief executive.

His popularity in the state was very high.

He had a close-knit political team and dedicated followers.

His heritage as the son of self-made immigrants was seen as a political plus.

Without New York Gov. Mario Cuomo, the Democratic field looked weak.

Fund raising would be simplified in a prosperous state, and would be further facilitated by Dukakis’s roots in the Greek-American community and by his wife’s Jewish background.

But even putting all these elements together, Grossman still couldn’t find the so-called ninth path to the White House. “It just wasn’t salable,” he thought at the time.

Rocky campaign trail

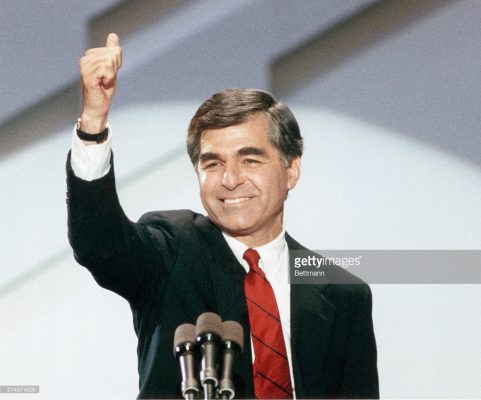

And indeed, Dukakis’s path has been steep and rocky since the triumphant July night in Atlanta when he accepted his party’s nomination.

Massachusetts is scrambling to stay out of red ink, and the budget problems have tarnished the governor’s reputation for competence, even in his own state. Despite having plenty of money, his political operatives are being criticized for bungling the campaign. Dukakis’s frequent reference to his Greek-immigrant heritage never quite caught on. Critics clamor for a campaign message, and political analysts say he lacks the warmth to embrace voters.

“The collapse of the campaign came suddenly, but the roots of it were there,” a longtime Dukakis observer says.

With nearly two weeks until election day, Dukakis’s campaign is by no means over. But many Democrats are acting as though they are attending a wake. With Dukakis’s poll numbers stubbornly lagging behind George Bush’s, and with what appears to be an even wider deficit in the Electoral College tally, political friends and foes alike are searching for clues to what went wrong.

“The thing that he didn’t learn from all of his Massachusetts experience is … warmth,” says author Richard Gaines. “The ability to touch people at an emotional level, either on television or hand to hand.” Mr. Gaines, now an editor with the weekly Boston Phoenix, is coauthor of a book on the governor entitled “Dukakis and the Reform Impulse.”

Few episodes in the campaign, Gaines says, have more clearly revealed Dukakis’s reserve and cool self-containment than his response to a question in the second presidential debate. Asked if he would support the death penalty for a hypothetical assailant who raped and murdered his wife, Kitty, Dukakis displayed no emotion, either in response to the grisly scenario or to what many viewers regarded as the questioner’s bad taste. Instead, the candidate delivered an analytical answer on why he opposes capital punishment.

It isn’t that Dukakis lacks passion, Gaines believes, but rather that he considers it inappropriate to wear it on his sleeve.

“He just assumes,” says another close observer, “that people see in him what he sees in himself.”

“We have learned that Mike Dukakis is not able to portray the characteristics of his humanity through the media,” says Jarol Manheim, a political scientist at George Washington University.

Professor Manheim says that the Bush camp has succeeded in running a nonintellectual campaign designed to appeal to voters’ gut feelings rather than to reason. The Dukakis people, on the other hand, have been trying to run a campaign based on reason rather than emotions. “The lesson is that the style of the Republicans works better,” the scholar says.

“He needs to speak with a kind of fervor,” says Heather Booth, a Dukakis supporter and president of Citizen Action, a coalition of state organizations dedicated to populist causes. “If you want people to fight for you, you have to sound like a fighter.” Ms. Booth adds that, uncomfortable with the political hyperbole that captures the evening news, Dukakis failed “to convey in concrete form the kind of tragedy that lies ahead.”

Many observers believe that Dukakis has, in fact, substantially improved his campaigning style in the waning weeks of the race. He has appeared more relaxed on the stump, they say, and has succeeded in projecting a warmer image.

These observers add that the refrain Dukakis has used in recent appearances – “We’re on your side” – conveys the commitment to a “caring” government that supporters say the governor stands for.

Nation’s shifting mood

Political analysts point to more than Dukakis’s personality, however, to account for his political problems. Running against a presidential candidate who is, in a sense, an incumbent, the Democratic nominee has had the difficult burden of convincing voters that, in a period of “peace and prosperity,” political change is nonetheless required.

In fact, there were early signs that the electorate would be open to this contention. Public-opinion surveys showed that many Americans were anxious about their economic future, even though they felt good about their current situation.

On the campaign trail, Dukakis complained about a “Swiss cheese” economy, in which some Americans were not benefiting from the general prosperity. He asserted that the nation’s apparent well-being was built on shifting sands of debt and trade imbalances.

Perhaps Dukakis has not delivered this message as effectively as he might have done. In addition, however, the public mood started to change. Beginning in late summer, polls showed that people were becoming more optimistic about the future. According to White House pollster Richard Wirthlin, “The perceptions that would underpin [the false-prosperity] theme were eroded out from underneath the Dukakis campaign.”

Still, many political analysts lay much of the blame for Dukakis’s woes at his own doorstep.

Author Gaines sees a parallel between Dukakis’s run for the White House and his second State House campaign. After first attaining the governorship in 1974, Dukakis lost his party’s primary in 1978. (He subsequently recaptured the office in 1982 and was reelected for a third term in 1986.)

“In the 1978 campaign,” Gaines says, “Dukakis forgot that in politics it’s a rare occasion when virtue is rewarded.” According to Gaines, the governor falsely assumed that because he tried to run an efficient and ethical administration, the voters would reward him with a second term, even though he had alienated many groups. Gaines says the same mistake happened after the Democratic convention, when the Dukakis people became complacent.

“I can’t really explain the lassitude after the convention, when the entire campaign was ceded to Bush,” says Gaines. “That’s a lesson he once learned and subsequently forgot.”

A penchant for detail

Another lesson Dukakis says he learned in his 1978 campaign was not to handle too many details himself. In John Sasso, Dukakis found a trusted lieutenant who lifted many political details from the candidate’s shoulders. But Mr. Sasso resigned from the campaign last year after his role in the “attack video” incident against a rival candidate, Sen. Joseph Biden Jr., was disclosed. With Sasso gone, Dukakis reportedly became mired in campaign minutiae.

“He again became his de facto campaign manager,” says Gaines, who says he was told by campaign insiders that for a time Dukakis insisted on meeting with every new hire, no matter how low-level their job. Sasso is back with the campaign and is widely credited with instilling new discipline and spirit. But it may be too little, too late.

From the time he first sought public office, Dukakis has been known as a meticulous organizer. That attention to detail could be seen in the Dukakis state operations as they moved from primary state to primary state. But some critics now say that during his long march to the nomination, Dukakis might have relied too much on structure, and not enough on message.

“They outorganized and outspent everybody in the primaries and figured they could do the same in the general election,” says Max Segal, the coauthor with Gaines of “Dukakis and the Reform Impulse.” He says the Dukakis people thought they could simply overwhelm Vice-President Bush with organization. “That’s the kind of thing you do after you have a message people buy into … [not] before the voters have developed an emotional liking.”

Also, Dukakis didn’t want to run what he considered a negative campaign, according to close friends. He assumes, they say, that the correctness of his cause is self-evident and will sell itself. It was not in his nature, nor was his staff ready, to respond quickly and effectively to the constant barrage of attacks from George Bush. Labeling Dukakis as being soft on crime, against the pledge of allegiance, weak on defense, and an out-of-the-mainstream liberal, the Republican political spin seemed to make the Dukakis campaign too dizzy to fight back.

“They don’t really understand the strategic aspects of a national campaign,” asserts Herb Asher, a political scientist at Ohio State University. “Dukakis just sort of sat back. … Maybe he thought those attacks were not worthy of his response, were beneath him.” As a result, Dukakis’s negative ratings shot up in national polls.

“You just don’t let your opponent have a clear shot at you like that,” Professor Asher says.

“He spoke to the programs and not to the vulnerabilities,” says Citizen Action’s Booth. “It was a campaign that was above the fray, full of ideas and programmatical alternatives.” She describes Dukakis as truly “of the people,” a man who understands working Americans. But his sense of caring just doesn’t come out in his personality, she says. It’s conveyed with the same cool efficiency the governor uses in public office. She laments that Dukakis never learned how to grab people’s emotions.

“That is probably the saddest thing in all of this,” says Richard Gaines. “Mike Dukakis is a man who has mastered more of the process of governing and political leadership than most politicians. He really does understand what a government does and how to serve the people better.” No matter what happens in the election, says Gaines, “You cannot take that away from him.”