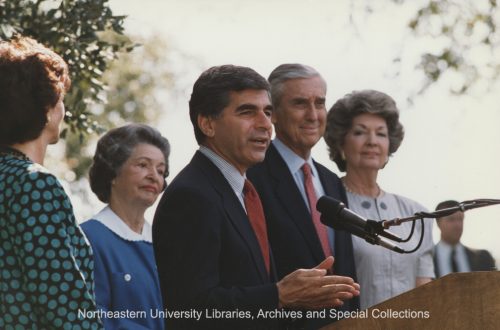

BOSTON — It has made Michael Dukakis a national figure and could make him president.

It has taken a state reeling from the collapse of its traditional manufacturing base and turned it into a booming high-technology economic model for the rest of the country.

It is the “Massachusetts miracle,” and there is no question of its phenomenal impact on this state: nearly 800,000 new jobs created in 12 years, unemployment at 2.9 percent, a 63 percent growth in personal income in the last seven years, taxes lowered, government services increased.

Rising from the depths of the 1974 recession, Massachusetts became a true American success story. But how much credit does the governor deserve for the state`s comeback, and what does it say about the kind of president he would be?

The topic has stimulated much debate as Dukakis turned the state`s economic rebound into the leitmotif of his presidential campaign. He brought Massachusetts back, his campaign theme goes; now he can do the same for the rest of the country.

Interviews with economists, local leaders and businessmen, however, lead to the conclusion that the state’s economic resurgence in the mid-1970s had its origins in the marketplace.

The fortunate confluence of academic and financial forces in the Boston area made it an ideal location for the emerging high-tech industry and reinforced the area`s leadership as a regional center for financial, educational and health services.

The comeback subsequently was nurtured by actions of Dukakis; Edward King, who served as governor between Dukakis’ first and second terms; a tax referendum that limited local taxes; and the federal government, principally through a large infusion of defense contracts.

Dukakis` chief contribution, in the opinion of many, was to use his office to bring the economic boom to older, depressed cities outside of the Boston area that otherwise might not have benefited.

Through a litany of alphabet-soup state agencies, Dukakis provided loans, grants, public improvements-even, in one case, a bus tour for out-of-town business leaders-to save such towns as Lowell, Taunton, Worcester,

Springfield, New Bedford and Pittsfield.

“Did he engineer it?” asked Richard Manley, president of the Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation, a civic watchdog organization. “No. Did he recognize it and build on it? Yes, he did.”

“It’s hard to exaggerate just how bad off the state was,” he said in an interview. “Economically, fiscally, psychologically, people were down, down on the future. ‘Taxachusetts,’ the New Appalachia-there was little sense of hope. And part of what a political leader does is part substantive stuff and part of it is beginning to rebuild confidence, building a sense of teamwork.” “An investment climate can be influenced,” said John Gould, senior vice president of Boston’s Shawmut Bank, “by a belief that there is a source in public policy that wants to make the economy grow. There’s no question in my mind that the governor has overtly and concretely showed that he is interested in helping the investment climate.”

The most comprehensive study of state government’s impact on the economy, published by Ronald Ferguson and Helen Ladd of Harvard`s Kennedy School of Government in May, 1986, gives Dukakis only minimal credit.

“Neither the scope nor the timing of recent policy initiatives in Massachusetts supports the view that they were an important catalyst in the remarkable economic turnaround of the past decade,” the study concluded.

“The turnaround in the unemployment rate reflects slow labor force growth and the capacity of the state’s private sector to respond to growing worldwide demand for certain goods and services. At the same time, state initiatives helped to attract growth to some depressed central cities and slow-growing regions, and may have helped at the margin to sustain the state`s revival once it began.”

When first elected in 1975, Dukakis found a state with an unemployment rate of 11.2 percent. The textile, leather and apparel industries, long the bedrock of the state`s economy, had fled to the South. And the oil embargo that sent the country tumbling into a recession had created a depression in oil-dependent Massachusetts.

As a liberal who came out of the reform wing of the Democratic Party, Dukakis often alienated the business community during his first term with his consumer and regulatory policies. But he also closed a state budget deficit approaching $1 billion through unpopular taxes and budget cuts, and he moved aggressively to revive the state’s economy.

He created numerous agencies to provide financing for small and emerging businesses. His administration built parking garages, roads, sewers and other public improvements to help localities attract private business.

He embraced an idea suggested by civic leaders in Lowell to turn their deserted textile mills into a state park. With $10 million in state funds, Lowell created Heritage State Park, which keyed a revival of the city’s struggling downtown and led to the creation of seven other urban parks around the state.

“He came down here with his Cabinet people,” said Mayor Richard Johnson. “He not only instilled in us the self-image we needed to build up ourselves, he also gave us the tools.”

The economic surge continued after Dukakis’ defeat for re-election in 1978 and allowed the state to weather the 1982 recession.

King, who succeeded Dukakis, was noticeably more pro-business. A voter referendum approved in 1980 limited local property taxes. And the Reagan administration’s military buildup increased prime military contracts to the state to nearly $10 billion in 1988 from $3.7 billion in 1980.

When Dukakis was elected again in 1982, he adopted a more open and friendly attitude toward business and initiated a new spate of economic development programs.

Most notable were Employment and Training Choices, which has provided training and jobs for 45,000 people who were on welfare, and a plant closing law under which business agreed to give 90 days notice for plant closings. Of the 13,000 laid-off workers who were given retraining under the law, three out of four have received jobs and their incomes average 87 percent of their former wages, according to the state Office of Economic Development.

Dukakis also helped depressed areas through a “targets of opportunity” program and established several “centers of excellence” around the state to stimulate combined academic and business research in such areas as genetics, marine sciences and microelectronics.

Ironically, just as Dukakis nears the Democratic nomination and the nation begins to focus on his Massachusetts record, a shadow has appeared over the state`s economy. Last week it was disclosed that the state faces a budget deficit that could reach $300 million in the current fiscal year and $200 million or more next year.

Dukakis said the gap was caused by a loophole in the state corporate tax and unexpected declines in capital gains taxes due to the new federal tax law. But critics note that the state economy has begun to cool slightly, and they blame the governor for spending too much and saving too little in an attempt to steady the state’s fiscal ship in a time of trouble and initiate a range of programs that, even if they did not create numerous jobs in the aggregate, infused the state with a sense of optimism and accomplishment it sorely needed.

Dukakis is sure to use his programs as models should he reach Washington. But Massachusetts is not the rest of the country. And it is unclear how well his ideas would work in depressed areas of states such as Ohio or Pennsylvania or Texas that do not have the economic diversity or the academic and cultural advantages that provided the seeds of Massachusetts’ rebirth.